Rocks that are formed from the molten state contain indicators of the magnetic field at the time of their solidification. The study of such "magnetic fossils" indicates that the Earth's magnetic field reverses itself every million years or so (the north and south magnetic poles switch). This is but one detail of the magnetic field that is not well understood.

The field lines defining the structure of the magnetic field are similar to those of a simple bar magnet. It is well known that the axis of the magnetic field is tipped with respect to the rotation axis of the Earth. Thus, true north (defined by the direction to the north rotational pole) does not coincide with magnetic north (defined by the direction to the north magnetic pole) and compass directions must be corrected by fixed amounts at given points on the surface of the Earth to yield true directions.

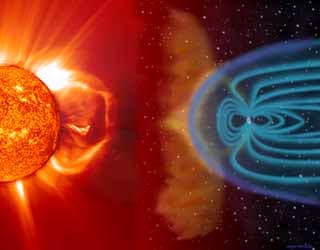

The solar wind is a stream of ionized gases that blows outward from the Sun at about 400 km/second and that varies in intensity with the amount of surface activity on the Sun. The Earth's magnetic field shields it from much of the solar wind. When the solar wind encounters Earth's magnetic field it is deflected like water around the bow of a ship.

The imaginary surface at which the solar wind is first deflected is called the bow shock. The corresponding region of space sitting behind the bow shock and surrounding the Earth is termed the magnetosphere; it represents a region of space dominated by the Earth's magnetic field in the sense that it largely prevents the solar wind from entering. However, some high energy charged particles from the solar wind leak into the magnetosphere and are the source of the charged particles trapped in the Van Allen belts.

Humans have used compasses for direction finding since the 11th century A.D. and for navigation since the 12th century. Although the North Magnetic Pole does shift with time, this wandering is slow enough that a simple compass remains useful for navigation.